Heya friendos! This week we’ll be exploring some narrative design issues I’ve found and solved for Clysmoids. We’ll be touching on how to decenter violence from games, the dissonance between tone and gameplay, and how to make things click.

How Am I Doing?

I’m doing great! I had a nice balanced week of social contact, exercise, downtime, and productivity. Just how I like ’em. In spite of this, I don’t have any particularly interesting personal, creative or design thoughts to share. So today I’ll just talk about some stuff I’ve been up to the past week.

Funny… I just realized that was the initial point of this newsletter: to bring updates on what I’ve been working on. It quickly became a journaling tool, where I share my thought process and examine my own behavioral patterns. Well, not today! Today we’ll just be talking about some narrative design on my mind.

What Am I Doing?

I’ve still been programming on Clysmoids and unfortunately don’t have anything of particular interest to share about it. It’s just connecting data through various game states and making sure it saves. I also had to rewrite the oldest code because I’ve made many changes to the framework over the course of this project.

Apart from that the narrative cohesion of Clysmoids has been on my mind. You see, I’ve been pitching it as “Darkest Dungeon meets ugly mutant Pokémon spa manager.” I’ve found that the spa manager part is what gets people most excited, and I’ve since been honing in on that aspect, at least thematically.

For the message, I want to tell people that the world will be fine, no matter how much humans mess it up. The setting is explicitly post-human: a future where humans are gone and the consequences of their actions mark the world, yet don’t dictate it. It has its own thriving ecosystem that’s alien from our own, with its own ruleset. I’m trying to make it an optimistic apocalypse that decenters our collective ego.

The hook is as follows. These mutants have a rough time hunting and gathering, so at the end of the day they just want to come home and relax with their friends. They also try to make new friends in the process.

A Vow of Non-Violence

That premise is pretty far removed from the early design. It made me realize how quickly game designers fall back on violence as a justification for their design choices. Combat is such a tried and true tool, that it’s easy to imagine a ruleset, mechanics, expectations, and character progression around it. All the things you need for engaging gameplay are right there, baked into this single concept. In-universe, all you have to do is physically fight whoever is in your way until they are no longer able to resist. It’s gruesome, domineering and unempathetic.

Pokémon has always been handwavy around its violence: you capture wild animals and make them fight against each other, but also they are your best friends and they “really don’t mind I swear!” With the advent of Palworld, which leans heavily into these aspects of violence (there are real-world guns and Pokémon slavery *sigh*), I feel compelled to make a vow of non-violence for Clysmoids.

Contact Sports

But… there is combat in Clysmoids. The very first prototype I did was that of turn-based tactical combat, and a huge chunk of the core design is built upon it. When designing some attacks, I already noticed I was trying to write my way around the problem. I named attacks things like Hug and Group Hug and Tickle. But in the end, you still essentially brawl these cute creatures into submission. There was a big divide between the cute but tragic tone of the narrative and the mechanics that center around power fantasy and survival.

So, I had to lock in an in-universe justification for mutants to engage in “combat” to have a cohesive narrative. Coincidentally, I was also looking for a way to justify the non-conventional turn system. Basically, your units stand on numbered tiles that indicate the turns in combat, and they can move between them to get another turn, at the cost of skipping one of your other unit’s turn and putting them in a more vulnerable position.

That specific interaction always made me think of dodgeball. Players move around to evade action, unless they are confident to take the heat. So I came up with the following: Clysmoids don’t fight, they participate in Tag Battles. A Tag Battle is supposed to be a playground sport: part competition, part ritual for making friends or rivals. You play on neutral ground. The rules are fast and loose and can change depending on who you’re playing against. There’s no referee, so things can get a little rough and there might be cheaters out there too!

Wording and visual feedback are important here. You don’t damage each other’s health until you are knocked out. You exhaust each other’s endurance until you give up. You don’t attack someone, you use a technique. This also gives me an excuse to implement a diegetic user interface. tTurn tiles can be drawn with chalk on the ground and the mutants physically move around on them.

Gifts

Then we come to another problematic aspect: capturing creatures. In Pokémon, you throw a ball at an injured wild animal that essentially imprisons them. It is implied the animal then builds trust and consent with the trainer, but nothing is explicitly explained. I had a hard time coming up with something similar for Clysmoids. First I had a Clysmocrystal, which was essentially an off-brand Pokéball. Then I wanted to do something with a collar, but of course, it made things so, so much worse.

But why are we trying to “capture” a creature? So that it comes back to the spa to relax? That doesn’t make much sense. If anything, we’re trying to befriend them! So, I asked around the Discord to see what could make a good “token of friendship”. Eduardo, who made Picma, an excellent meditative puzzle game, suggested a friendship bracelet. The thought of bribing someone you’re competing with in sports with a friendship bracelet is so funny and wholesome to me, that I have no choice but to go with that.

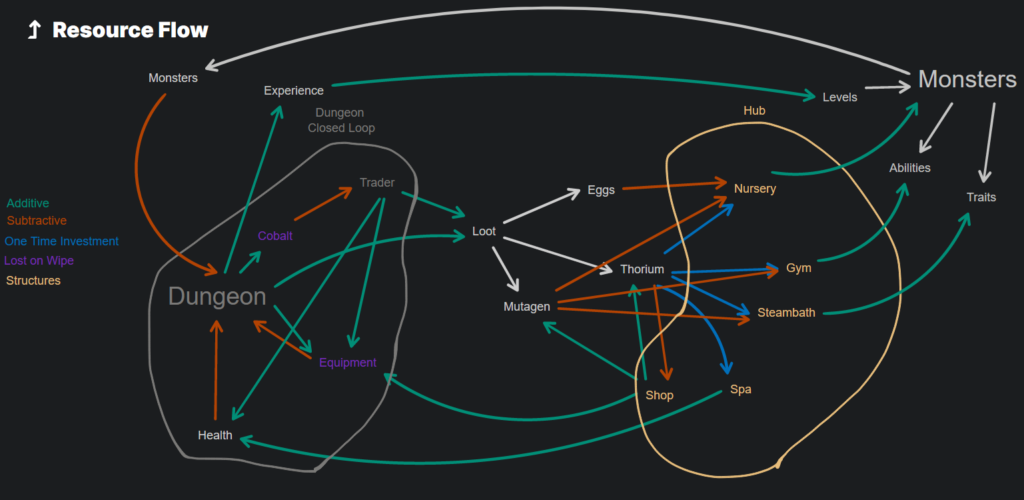

But there was another problem. A game like Clysmoids has core aspects that feed into each other: exploring a dungeon gives you rewards to spend in the spa, to make you stronger for the next dungeon, that gives you more rewards for the spa, ad infinitum. There wasn’t a big variety of rewards, and it made every dungeon run feel the same. If you’re just grinding for 3 types of resources, it doesn’t feel rewarding or exciting at all.

So, I had to diversify the rewards. A lot of what I like about creature collection games is the categorization of different types: their physiology, behavior, personality, etc. Naturally, not every person would like to receive a friendship bracelet, so this seemed like a good point to think of more options for rewards.

The idea is that each individual Clysmoid has a preference for one of three types of gifts: Snacks, Flowers, or Shiny Things. A friendship bracelet or other jewelry would be shiny things, snacks could have boxes of chocolates and bags of chips and flowers would have bouquets of mutated flora, for decoration or consumption. I’ve yet to test any of this, but narratively speaking, I think this is the way to go!

Why Am I Doing? (this)

As game makers, we’re constantly trying to make things click. It’s that moment when pieces of the puzzle start fitting together. Having many minor problems in design is often a symptom of dissonance between different visions. If you settle on a unified vision that is cohesive between narrative and game design, it helps identify these problems, usually with solutions that tackle more than one.

Huh, I guess in the end I did have some interesting thoughts to explore…